Ecological traits predict population trends of urban birds in Europe

June 14, 2024

Urban ecology is a widely studied phenomenon, particularly in the last few decades. Following plants, birds are the second most studied taxa in urban ecology research due to their omnipresence and easy detection in the field. Surprisingly, despite extensive knowledge of urban birds' breeding biology, physiology, and community ecology, their population dynamics have been highly understudied. In the present study, published earlier this year in Ecological Indicators, the authors aimed to test which ecological traits influence the national trends of 95 bird species that frequently breed in urban areas of 18 European countries, using data from the Pan European Common Bird Monitoring Scheme (PECBMS).

Species react differently to urbanisation, resulting in specific urban bird communities in cities that also change over time and space. It is also evident that species colonised cities in various historical periods. For instance, the House Sparrow (Passer domesticus) was linked to urban settlements long before the industrial era. At the same time, the Wood Pigeon (Columba palumbus) started its successful urban journey only in the last few decades. The timing of urbanisation might have been connected to changes in cities. For example, increasing green cover might favour forest species and, on the other hand, disfavour open landscape species. Subsequently, this might result in different long-term population trends among specific groups of birds that invaded cities during certain periods.

Additionally, the extent of urban affinity differs among species. Some species are highly urbanophilous and inhabit almost exclusively cities and other urban settlements, while other species inhabit urban areas only occasionally or never. Traditionally, the birds were divided into three categories based on their urban affinity: urban exploiters (the majority of the population in human settlements), urban adapters (a significant portion of the population in both urban and rural areas), and urban avoiders (no considerable portion of the population in urban areas). In recent research, this categorical approach is being replaced by continuous measures, such as species occurrence in areas of artificial light (Callaghan et al. 2019) which enables a more accurate estimation of species’ affinity to urban settlements.

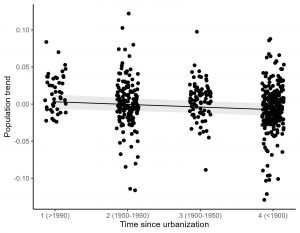

The present study tested whether these two urban predictors (time since urbanisation and relative urbanness score) and their interactions with other ecological traits influence the national long-term population trends of 95 bird species that frequently breed in urban areas of 18 European countries. The analyses using generalised linear mixed models showed that birds that colonised cities earlier have more negative population trends than birds that colonised cities more recently. This implies that the change in the city environment causes different conditions for birds, and the species that colonised cities a long time ago face challenges in maintaining their urban populations. For instance, the efficient removal of available organic waste and farm animals from cities might result in a decline in species dependent on these food sources and birds that rely on crevices or cavities in buildings, gradually disappearing from city centres. On the other hand, some recent colonisers, such as corvids, might thrive from the ban on persecution that occurred only recently in some European countries.

Fig 1: The relationship between population trends of European bird species breeding in urban areas and time since their urbanization. The higher the value, the longer the time since urbanization. The results are estimated by a generalised linear mixed model. The 95% confidence interval is shown.

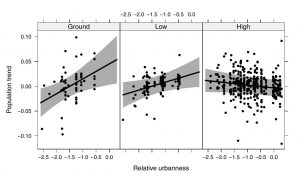

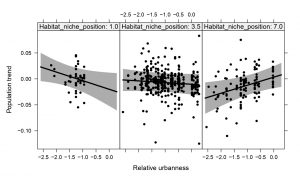

Open-landscape urbanised species had more positive population trends compared to urbanised forest-dwelling species. This implies that urban greenery does not fully support forest species; instead, mid-range generalist species are favoured. Also, the use of non-native plant species could lead to a limited number of forest species capable of inhabiting urban areas. Another mechanism in the observed pattern could be agricultural intensification, which leads to more pressure on open-landscape birds and results in urban areas being refugia for these species since agricultural management is less intensive in human settlements. Some urbanised open-landscape species, such as the Marsh Warbler (Acrocephalus palustris) and the Greater Whitethroat (Sylvia communis), could benefit from suitable habitats in cities, such as brownfields and construction sites. The less urbanised open-landscape species typically do not take advantage of these habitats, e.g., the Yellow Wagtail (Motacilla flava) or the Skylark (Alauda arvensis).

Fig 2: The relationship between population trends of European bird species breeding in urban areas and their relative urbanness in the interaction with species’ nest site. Relative urbannes expresses species’ association with urban areas; the higher the value, the more urbanized species. The figure is divided into three parts according to the nest site selection: breeding on the ground – left, breeding close to the ground in shrubs and low vegetation – centre; breeding high above the ground on trees or buildings – right. The results are estimated by a generalised linear mixed model. The 95% confidence intervals are shown.

Urbanised ground-breeding birds had more positive population trends than urbanised birds that do not nest on the ground. This pattern might be surprising since good scientific evidence shows ground-nesting birds are disadvantaged in urban settlements. However, the ground-breeding birds that have been urbanised for centuries, such as the Mallard (Anas platyrhynchos), have already adapted to the specific hazards of breeding in urban areas, allowing them to persist well in cities. Species vulnerable to the risks of ground breeding in cities are not urbanised at all and, therefore, are not considered in the data. Similarly, as mentioned above, this pattern might also result from agricultural intensification, which leads to cities acting as refugia for open-landscape species. Finally, wetland birds might contribute to this pattern, as many wetland species have colonised cities, and breeding in wetlands usually occurs on the ground. In contrast, modern buildings are generally unsuitable for breeding birds, such as the House Martin (Delichon urbica) or Eurasian Jackdaw (Corvus monedula), and the vegetation in urban parks is carefully managed for ornamental and safety purposes. This might result in weaker performance of birds that do not breed on the ground. Altogether, these mechanisms could provide explanations for the observed pattern.

Fig 3: The relationship between population trends of European bird species breeding in urban areas and their relative urbanness in the interaction with species’ habitat niche position. Relative urbannes expresses species’ association with urban areas, the higher the value, the more urbanized species. Habitat niche position is the gradient from forested landscape (lower values) to the fully open landscape (higher values). The results were estimated by a generalised linear mixed model. The 95% confidence intervals are shown.

This study is novel in investigating the patterns underlying the population dynamics of urban birds and linking them to ecological traits. However, caution should be taken regarding the results, as national trends were used instead of urban-specific trends. Further research on urban population trends is needed to support the results of this study.

The authors are heartily thankful to the PECBMS coordinators and all the volunteers who enabled this study to happen.

Jan Grünwald

How to cite the article:

Jan Grünwald, Ainārs Auniņš, Mattia Brambilla, Virginia Escandell, Daniel Palm Eskildsen, Tomasz Chodkiewicz, Benoît Fontaine, Frédéric Jiguet, John Atle Kålås, Johannes Kamp, Alena Klvaňová, Lechosław Kuczyński, Aleksi Lehikoinen, Åke Lindström, Renno Nellis, Ingar Jostein Øien, Eva Šilarová, Nicolas Strebel, Thomas Vikstrøm, Petr Voříšek, Jiří Reif: Ecological traits predict population trends of urban birds in Europe. Ecological Indicators. Volume 160, 2024, 111926, ISSN 1470-160X.

Article link: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2024.111926

Literature:

Callaghan CT, Major RE, Wilshire JH, Martin JM, Kingsford RT, Cornwell WK. Generalists are the most urban-tolerant of birds: a phylogenetically controlled analysis of ecological and life history traits using a novel continuous measure of bird responses to urbanisation. Oikos. 2019; 128(6):845–858. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/oik.06158